I’d pored over The Mysterious Affair at Styles, Agatha Christie’s first novel, for days before I finally allowed myself to turn to the page that revealed the identity of the murderer. I’d created a timeline, compared characters’ alibis, thrown out red herrings, interpreted the trickiest of clues. I’d delighted in the twists and turns of the plot, the moments of high drama, Poirot’s cryptic murmurings.

Only to reach the wrong conclusion.

Well then, you were outsmarted.

Not at all. The Mysterious Affair at Styles is a brilliant book, a delightful mystery that plays on the reader’s assumptions to direct suspicion first toward, and then away from, the murderer. But with all of my attention to the details of the crime, I could have arrived at the correct solution to the mystery only if I had already known how strychnine interacts with potassium bromide (I did not know). Styles is a satisfying read—but it is not a satisfying mystery.

In fact, over the course of the past several years, I’ve read many good mystery novels that are not good mysteries, while participating in a very exclusive murder mystery book club. (It’s just me and fellow author Traci Chee in the club, and only because we’re the only ones we know who are obsessive enough to try to solve every mystery we read.)

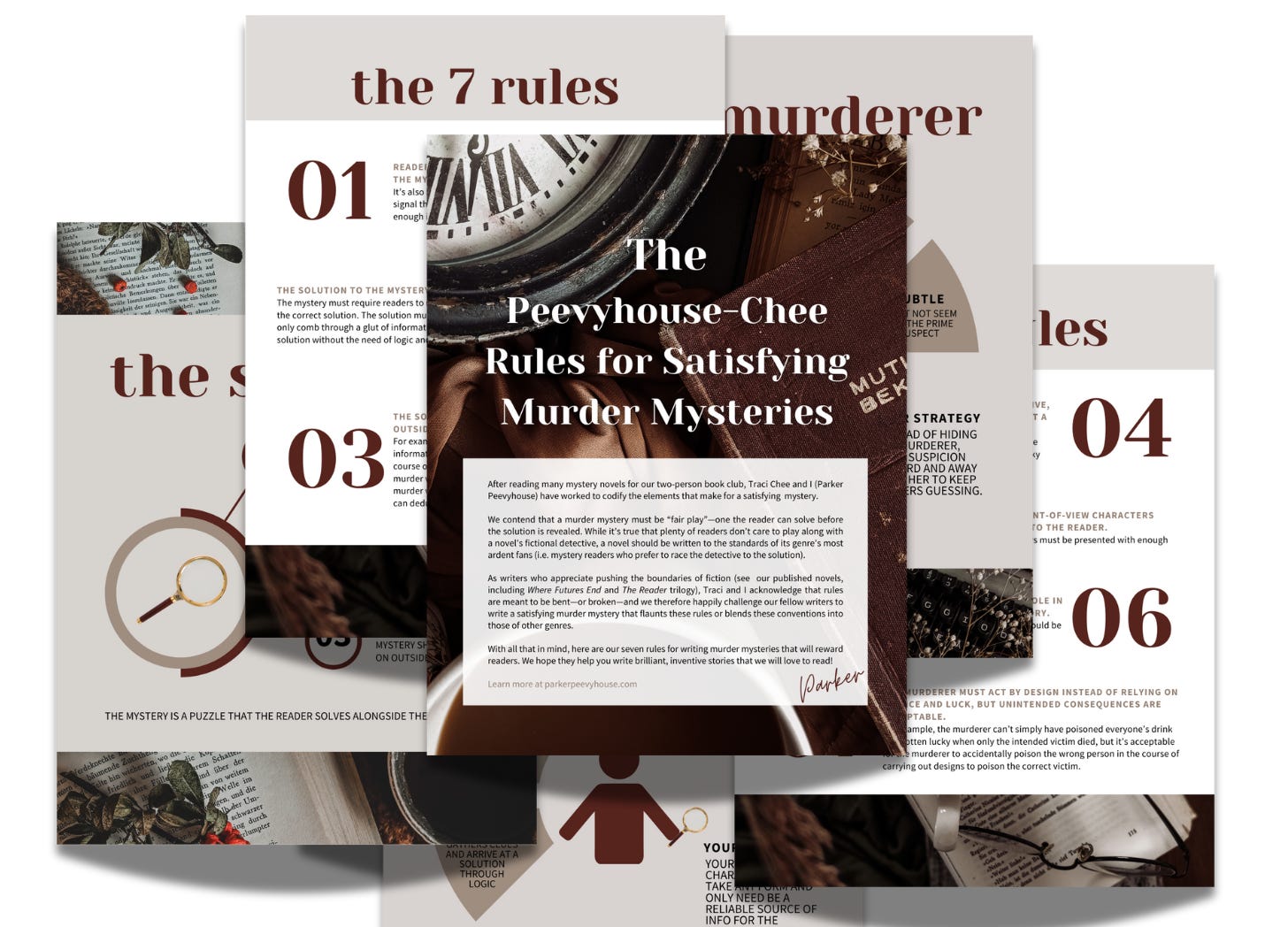

In that time, my club (again, just Traci and I) has worked to codify the elements that make for a satisfying mystery. They are seven in total. I’m urging politely asking writers to consider our seven rules so that mystery readers like me can avoid the disappointment that comes with realizing you’ve spent a whole lot of time trying to solve a false puzzle.

Knox’s Decalogue and Van Dine’s Rules

First, you should know that Traci and I aren’t the only writers who have attempted to codify the “fair play” murder mystery (one that can be solved by readers alongside the detective). In the 1920’s, mystery writer Ronald Knox published his Ten Commandments for Detective Novelists, which he wrote for a group of writers (including Agatha Christie) who later became The Detection Club. Knox’s Decalogue included such rules as these:

“Not more than one secret room or passage is allowable.”

“No hitherto undiscovered poisons may be used, nor any appliance which will need a long scientific explanation at the end.”

Around the same time, mystery writer S. S. Van Dine published his Twenty Rules for Writing Detective Stories, which included broader mandates like these:

“The reader and detective must have equal opportunity for solving the mystery.”

“The criminal must be found out by logical deduction — not by accident, coincidence or unmotivated confession.”

Over the course of reading quite a few murder mysteries for our book club, Traci and I have decided that we don’t agree with all of Knox’s rules (“The detective must not himself commit the crime.” Christie pulled this off so brilliantly in one of her novels!) or all of Van Dine’s rules (“No romance.” Why not?). We also think their rules, and other lists of rules for “fair play” murder mysteries, are not complete.

We feel that we have pinpointed exactly what makes for a satisfying mystery novel, which we contend must be “fair play”—one the reader can solve before the solution is revealed. While it’s true that plenty of readers don’t care to play along with a novel’s fictional detective, a novel should be written to the standards of its genre’s most ardent fans (i.e. mystery readers who prefer to race the detective to the solution).

As writers who appreciate pushing the boundaries of fiction (see Where Futures End and The Reader trilogy), Traci and I acknowledge that rules are meant to be bent—or broken—and we therefore happily challenge our fellow writers to write a satisfying murder mystery that flaunts these rules or blends these conventions into those of other genres.

With all that in mind, here are our rules not for writing a murder mystery in general (we’re not trying to describe the genre itself) but for writing murder mysteries that will reward readers.

The Peevyhouse-Chee Rules for Satisfying Murder Mysteries

Readers must have access to enough clues to solve the mystery before the solution is revealed. It’s also helpful (but not required) for the narrator or detective to clearly signal the point in the story when readers have been presented with enough information to solve the mystery.

The solution to the mystery must reward cleverness. The mystery must require readers to use deduction and logic to arrive at the correct solution. The solution must not be apparent to readers who only comb through a glut of information for details that reveal the solution without the need of logic and deduction.

The solution to the mystery should not rely on outside knowledge. For example, if poison was used to commit the murder, all necessary information about the poison should be presented to readers during the course of the story. Likewise, if the author invents a poison or other murder weapon (like a complicated gadget), information about such a murder weapon must be presented to readers to the extent that readers can deduce the way in which the weapon functions.

There must be a character who serves as a detective, and this detective must gather clues and arrive at a solution through logic. The solution to the mystery must not rest mainly on information the detective has gained through supernatural agents, hunches, or lucky accidents.

The detective and other point-of-view characters must not intentionally lie to the reader. Omissions are acceptable, but readers must be presented with enough clues to deduce truth from lies.

The murderer must play a somewhat significant role in the story and must be introduced early in the story. Even if the murderer doesn’t seem like a prime suspect, readers should be familiar with the character.

The murderer must act by design instead of relying on chance and luck, but unintended consequences are acceptable. For example, the murderer can’t simply have poisoned everyone’s drink and gotten lucky when only the intended victim died, but it’s acceptable for the murderer to accidentally poison the wrong person in the course of carrying out designs to poison the correct victim.

Paid subscribers can download a full-color pdf version of The 7 Rules For Satisfying Murder Mysteries at the bottom of this post.

Workshop: Applying the Peevyhouse-Chee rules to And Then There Were None

Let’s see how Agatha Christie’s beloved murder mystery, And Then There Were None, follows the seven rules for satisfying murder mysteries. Very many SPOILERS AHEAD.

And Then There Were None is about ten strangers who arrive on the secluded Soldier Island, where they are greeted only by a gramophone recording that accuses each of them of a terrible past crime. Over the course of the next few days, the strangers die one by one, murdered by someone so clever and stealthy as never to be detected by the group. And yet, no one else has access to the island, meaning the murderer was among the victims. How?

If you haven’t read the book, please go read it now before continuing onto the spoilers! It’s short and fun and utterly brilliant. Stop just after the epilogue and try to solve the mystery before you read the “manuscript” section, which reveals the answer.

What makes And Then There Were None such a satisfying mystery? Let’s apply our rules:

1. Readers must have access to enough clues to solve the mystery before the solution is revealed.

The first half of And Then There Were None provides few opportunities to narrow down the suspects. Anthony Marsten is poisoned by cyanide, but all of the other guests to the island had access to his whiskey, so any of them could have slipped the poison into his glass. Mrs. Rogers dies in her sleep from an overdose anyone could have orchestrated, and a couple more victims are bludgeoned by objects anyone might have accessed.

But the story bottlenecks in a few key places:

Only three characters were alone with Justice Wargrave before he was found dead, which indicates that no other suspects can be considered any longer.

The revolver used to kill Wargrave is returned to its original place, which narrows down the list of suspects even further.

The eighth victim, Blore, is killed when a marble clock is pushed out a window and falls on his head—and yet the only two remaining suspects were together when this happened, so neither could have committed the crime!

Believe it or not, these are the only clues a person needs to solve the murder. Here’s why…

2. The solution to the mystery must reward cleverness.

The solution to And Then There Were None is very rewarding because it can’t be arrived at simply by reading closely enough to spot it among other details. Instead, the reader must first understand that the clues listed above seem to prove that no one can be the murderer. Since the epilogue insists that’s not the case, the reader must go back and realize which false assumptions she has made.

The solution to the mystery comes in the moment after Wargrave is found dead. Only the doctor, Armstrong, examines the body very closely. He declares Wargrave dead from a gunshot wound. Since we assume doctors understand such matters—and are generally trustworthy—we take his word for it. But Wargrave isn’t dead. He’s faking his death, having convinced Armstrong to play along.

When the reader spots this false assumption (Wargrave is dead because the doctor says so), she can conclude that Wargrave was the one who killed everyone on the island, including himself last of all, in secret.

3. The solution to the mystery should not rely on outside knowledge.

Readers need no knowledge of cyanide to understand that Marsten could have been poisoned by any of the nine remaining strangers. Likewise, they need no knowledge of gunshot wounds to guess that Armstrong lied when he declared Wargrave dead. Readers need only deduction to figure out how to eliminate suspects by the end of this novel.

4. There must be a character who serves as a detective, and this detective must gather clues and arrive at a solution through logic.

And Then There Were None is unusual in that the detective doesn’t show up until the epilogue. Usually, we see the detective arriving either at the start of the mystery novel or about halfway through, at which point he conducts interviews and inspects crime scenes for the benefit of the reader.

But in And Then There Were None, the suspects/victims are the ones who search the island and scour for clues. Still, we do finally hear from Inspector Maine in the epilogue, where he lays out every important clue and debunks every tempting but incorrect theory. It’s through Maine that Christie signals to the reader that the murderer was one of the ten victims and that the reader is now ready to answer the question Maine poses at the end of the epilogue: “Who killed them?”

5. The detective and other point-of-view characters must not intentionally lie to the reader.

Every suspect/victim in And Then There Were None is also a POV character—and yet one of them is secretly a murderer. How is that the murderer doesn’t give himself away in the sections that follow his POV?

The story opens with Wargrave traveling to Soldier Island. He draws a letter from his pocket and reads the “practically illegible” invitation to the island, signed by a Lady Culmington. It would seem he’s an unsuspecting guest, not a a clever killer who has orchestrated everyone’s eventual arrival at the island.

But Wargrave’s thoughts never indicate that he received this letter. Instead, he tries to “remember when exactly he had last seen” Lady Culmington and reflects that she “was exactly the sort of woman who would buy an island and surround herself with mystery.” He doesn’t lie to the reader, because he never says that Culmington actually bought an island or that she even wrote the letter. In retrospect, he seems to be reflecting on the idea that his forged invitation to the island should be convincing enough to fool his victims into thinking he’s another unwitting dupe.

6. The murderer must play a somewhat significant role in the story and must be introduced early in the story.

The murderer, Wargrave, is the first character introduced in the novel, and he often weighs in on the unfolding events. The only reason not to suspect him is that he’s “murdered” halfway through the book! In this way, Christie relies on our assumptions to lead us wrong (“The doctor declared Wargrave dead, and I can trust the doctor”) instead of simply hiding the murderer from our attention.

7. The murderer must act by design instead of relying on chance and luck, but unintended consequences are acceptable.

The murderer has obviously gone through a lot of trouble to lure his victims to Soldier Island, and to poison, shoot, push, and bludgeon them in ways the other victims won’t detect. Many of Wargrave’s deadly designs are very simple: he drops a heavy clock onto someone from a window, he slips poison into a drinking glass, he shoves someone off a cliff.

Some of his machinations are harder to believe: he leaves a noose in Vera’s bedroom when she’s feeling especially guilty and grieved, and depends on her to hang herself. But had Vera failed to hang herself, we can imagine Wargrave would have tried a Plan B.

The most trying aspect of the novel is that none of Wargrave’s plans seems to go awry, and no one ever notices that he’s sneaking around dropping things on people’s heads. But a little suspension of disbelief isn’t a terrible thing to maintain on the way to such a satisfying solution.

In the end, what makes And Then There Were None an enduring mystery novel is that it gives the reader a fair chance to solve a very cunning—and fair play— puzzle.