Sorry, but I just don’t buy it.

That’s now how things work.

That’s not how people act.

(Things readers say right before they put the book down and never pick it up again.)

Today, we’re going to work together to avoid those dreaded scoffing noises. Let’s talk about how to fix the holes in your story’s logic.

Technical Details Are Important, But…

I recently tried watching the new Hulu science-fiction thriller Paradise, the first episode of which ends with a huge twist: [SPOILER] the picture-perfect town that serves as the setting is actually located underground and its inhabitants are survivors of a planet-wide disaster. When I reached this twist, I scoffed. It just isn’t possible that the government could have excavated a space large enough to fit parks and houses and an airy, sky-like dome. And it doesn’t make sense that the houses in these towns are full of nick-knacks and candles and notebooks. A bunker-town would be small, spare, and energy-efficient.

I tried watching the second episode, and it wisely started with a flashback to a city planner voicing my exact concerns. That character is then taken to the excavation site for what will soon be the bunker-town and he sees with his own eyes that a team is digging under a mountain in order to create a huge town. But how is this large-scale excavation possible? They didn’t say (because it’s not!). I turned off the show. [END SPOILER]

But here’s the thing—if the premise of a show is technically impossible, you don’t need to despair. Technical plausibility is the easiest thing to fix: you do some research or interview an expert, and you revise. I used to really worry when I would find logical issues in my stories, but I’ve come to realize that any technical problem can always be fixed with enough thought or research.

The hardest part of this process is realizing you have a hole in your story’s logic to begin with. That’s why we show our manuscript to varied (trusted!) critique partners. It one person doesn’t buy in, consider tightening those details. If more than one person doesn’t buy in, definitely tighten.

But the most crucial thing to know is this: air-tight technical details are less important for your premise than emotional resonance.

Readers Care Most About Motivations

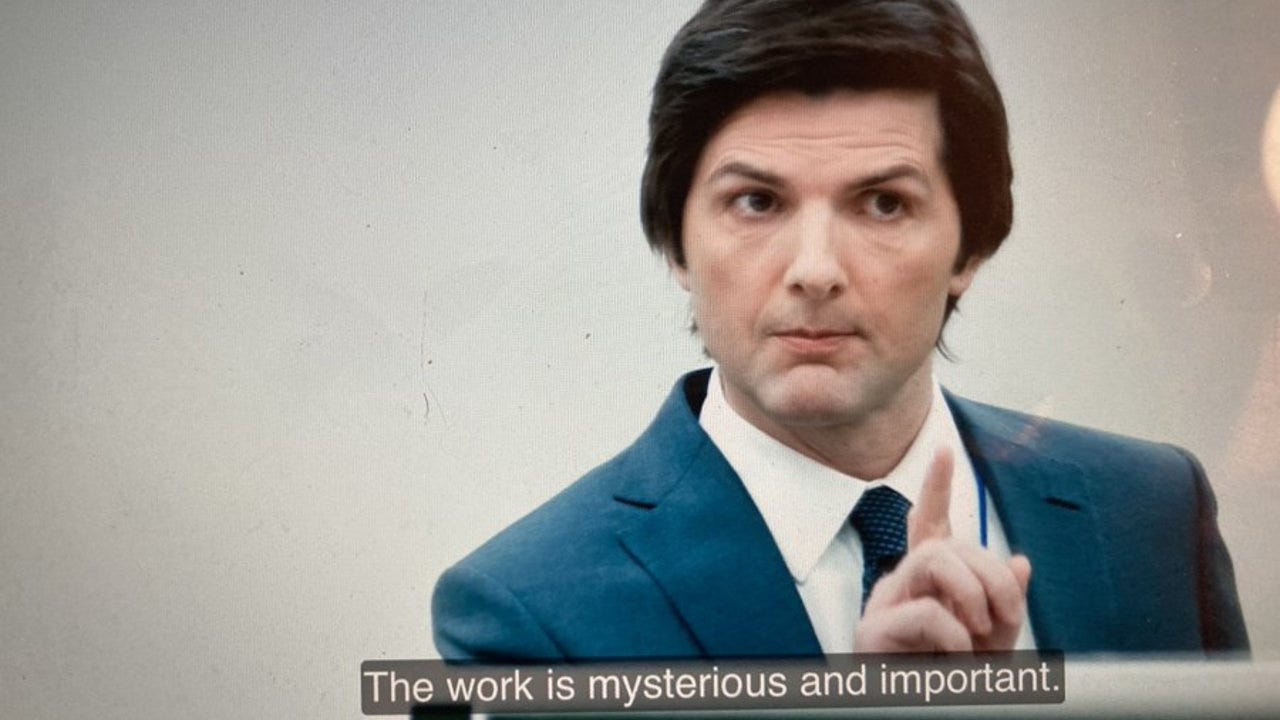

Why does anyone buy into the premise of the show Severance? It’s one of my favorite TV shows but its premise isn’t technically possible: a company severs the consciousness of its workers so that they aren’t aware of their work life while they’re at home (and vice-versa). Obviously, such a procedure isn’t possible. But because we know it’s not possible, we’re willing to buy into it the same way we’re willing to buy into the idea that a wizard can wield magic—it’s a bit of a fantasy.

You can’t get away with the same thing when it comes to a premise that’s closer to reality. You can’t tell readers that your two love interests are forced to share a bed at a hotel if we suspect they could simply bring in a cot. You have to make it clear there are no other possible options: no cots, no couches, etc.

But either way, what readers will really focus on is the motivations of everyone involved in the premise. That includes personal and societal motivations.

Two Types of Motivations

In Severance, the characters need to have believable personal motivations for wanting to sever their conscious minds between their work life and home life. The show’s main character, Mark, is grieving his wife and sees severance as a way to escape from his overwhelming sense of loss. While he’s at work, he has no idea that his wife is dead, or even that he was ever married.

We also need a societal reason for this procedure—and that’s where the show falls short, in my opinion. I’m willing to buy into the idea that a company would want to use severance to keep its secrets, especially since I live in the Silicon Valley, where it seems every worker is required to sign at least one NDA in her lifetime.

But in Severance, employees have no idea what work they’re actually carrying out even while they’re in the office. Mark sits at a computer all day and clicks on mysterious numbers by deciding which ones feel “wrong.” He doesn’t know why he’s “refining” this “macrodata” (vague terms that perfectly capture corporate-speak). So why does he need to be severed? What secrets could he possibly reveal to the public considering he knows nothing about the numbers he’s clicking on? It’d doesn’t quite make sense. (But I’ll revisit this issue in a bit!)

Let’s look at how personal and societal motivations affect the premises of a few other stories…

Societal Motivations: One Example

The 100, one of my favorite past TV shows, is set in the future, after a nuclear apocalypse has forced people to flee onto space stations. Now that generations have passed, the stations have become over-burdened, and resources are dwindling. But no one knows whether it’s yet safe to return to the earth’s surface.

So they send down a few science-minded survivalists to check things out, right?

No. They send teenagers.

Truly, this shouldn’t make sense. What kind of society is willing to send children to their possible deaths? Or to rely on children to accomplish a task crucial to the survival of the human race?

But this is a teen show, so teens must be our main characters. In fact, most YA novels suffer from this same weakness: a teen must be the one to solve the major problems in the story, even when it would make more sense for an adult to take charge. (As a writer who has published three YA novels, I have spent a lot of time thinking about how to get around this!)

The 100 justifies its premise by making the teens delinquents. They’re causing trouble aboard the station, so if they never return, at least the station won’t have to deal with them anymore.

While this explanation isn’t completely satisfying, it works well enough. It gives the leaders of the space station a stronger motivation for sending teens rather than trained adults. And since we know we’re watching a teen show, and we want the teens to lead the story, we’ll go along with this premise.

Societal Motivations in Mysteries, Thrillers, Rom-Coms, and Science Fiction

Writers of mysteries and thrillers always have to answer the question, Why not just leave this to the police? The answer is usually that the police are incompetent or corrupt. Or the characters have something to hide from the police and therefore don’t want them involved.

Sometimes the police are involved, alongside the main character. It’s hard to believe that the police would allow an amateur detective to accompany them on their investigations; there isn’t really any such thing as a “consulting detective.” But if we feel the amateur has special insight—a meticulous attention to detail, a genius IQ, special knowledge of the suspects or location—we’ll allow this bending of the rules.

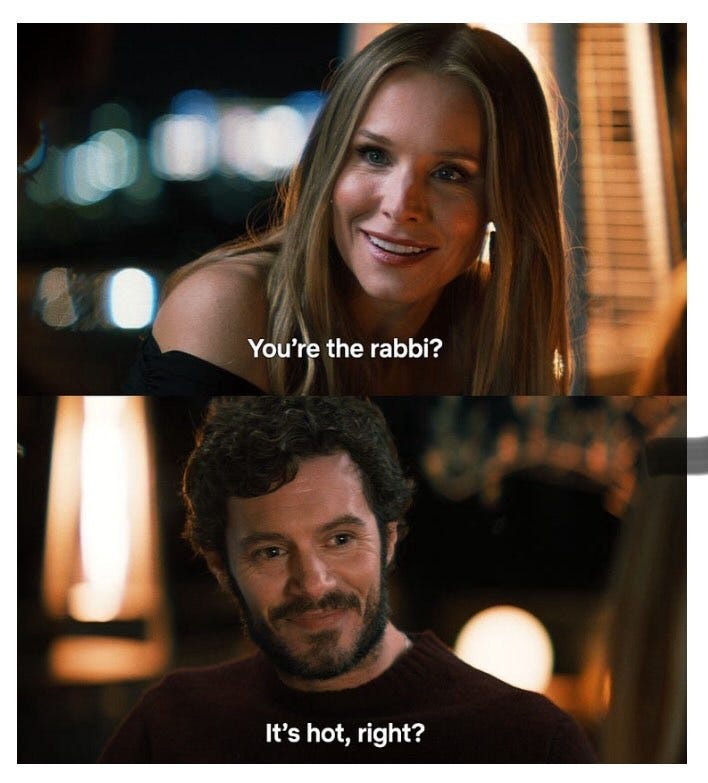

Societal motivations can also apply to smaller communities. In the hit Netflix rom-com Nobody Wants This, Noah’s parents want him to marry a Jewish woman, while Noah wants to date Joanna, who isn’t Jewish. If Noah stays with Joanna, he risks not only disappointing his family but also jeopardizing his dream career as head rabbi.

Contrast this with another Netflix rom-com, Our Little Secret, in which Avery arrives at her boyfriend’s house for Christmas only to realize her ex, Logan, will also be spending the holidays at the house—because he’s dating Avery’s boyfriend’s sister. Avery and Logan immediately decide that they must not tell anyone that they previously dated, which becomes the major source of conflict for the show. Why can’t they tell their partners’ family that they used to date each other? Why would the family care? I never could figure that out.

You might be tempted to gloss over societal motivations in your story, but motivations at this large-scale level put pressure on characters—and that pressure makes a story more interesting. The amateur detective must compete with the police; the budding romance must withstand a family’s expectations. The teens must survive not only a post-apocalyptic landscape but also the unpredictable aggressions of their fellow delinquents.

To me, some of the most interesting scenes in Severance are the ones that give us a glimpse at what society at large thinks about people who have gone through this mind-splitting process. Mark runs into protestors who think the procedure is gruesome. He has to suffer through parties at which people debate whether he has been the victim of something unethical. He must contend with a sister who suspects something isn’t right at his workplace. There’s no reason society would accept such a radical procedure without comment. And these comments make the show more interesting.

If you haven’t yet considered character motivations on this level, you might want to explore this angle and see what kind of clarity and complexity it adds to your novel.

Character Motivations

I have a problem with clone stories. Although I tend to like them because they bring up interesting questions about what it means to be human, I can’t fully buy into the premise that anyone would go to all the trouble to clone a human just to harvest his organs (which is always the justification given for cloning). It would cost so much money, and take so much time, when stealing organs from regular people would be cheaper and easier and is something that actually happens right now in the world. Obviously, stealing a person’s organs is very wrong, but so is raising a human to be harvested—if a society is unwilling to do one, why would it be willing to do the other?

My favorite novel featuring characters who are clones is [SPOILER but I think everyone knows this] Never Let Me Go by Kazuo Ishiguro. The reason I love this novel, despite the fact that I don’t believe society will ever go to the trouble of cloning humans just to harvest their organs, is that it explores character motivations in a very poignant way: If you knew you were destined to die in your twenties, how would you live your life? If you found out you were a clone, what would you want to know about the person you were cloned from? If you lived your life apart from society, what would you want to experience before you died?

But in order to explore the reasons the characters fall in love, make art, and plead for a stay of execution, the premise has to be pretty tight at the character level. Once the characters learn that their organs will be harvested, why don’t they run away?

Some clone stories, like the mildly campy film The Island, focus almost entirely on clones trying to escape. Others, like the award-winning YA novel The House of the Scorpion by Nancy Farmer, focus at least partly on escape. But Never Let Me Go is a more meditative story that needs to sidestep the idea of escaping. The movie adaptation includes a brief moment when the characters are shown tapping a bracelet against an electronic surveillance sensor. But the book never address the issue. Instead, it’s implied that because the characters have grown up in their role as organ “donors,” they have learned to accept it.

Their understanding of their fate is contrasted with the central question of the novel: Do clones have souls? Even while the characters try to find a way to prove that they do indeed have souls and therefore shouldn’t be executed, they contend with the societal belief that they are soulless. Possibly, the clones themselves aren’t even truly convinced of their own humanity—and so why would they run away?

Leaving Room for Poignancy

Such simple character motivations tend to allow room for this kind of poignancy. In Severance, we know that Mark agrees to be severed in order to escape the loss of his wife, but his office mates have different motivations. In Season 2, it’s implied that Dylan underwent severance because he wasn’t able to get a higher-paying job with which to support his wife and three children.

Surprisingly, this motivation lends just as much poignancy to the show as Mark’s. Dylan is granted visitation from his wife while he’s at work, but he doesn’t have any memory of her. He longs to connect with her, asking if she will allow him to hug her, a request that partially baffles her since she’s quite used to her husband hugging her when he’s at home. At one point, she shows him a photo of their family taken in cowboy costumes, the kind of sepia-toned photo you pay for at a theme park. With no memory of the outside world to help him understand the context of the photo, he says, “So we live on a ranch?”

In finding ways to clarify and strengthen your characters’ motivations, remember to make their motivations simple enough to allow room for poignancy.

Your Turn

If you’re looking to fix holes in your story’s logic, ask yourself these questions:

Which points in my story do critique partners finding confusing or difficult to connect with? How might I improve technical details to address those points?

What do my main character’s family members or friends think of her situation? What about her boss at work, or her neighbors, or other members of her society?

How can I simplify my main character’s motivation so that a child might understand it? How might I make it more poignant?

Next Week: Character Motivations That Don’t Work (and how to fix them)

In Part 2 of this series, we’ll cover some common pitfalls of story motivations:

over-motivating characters

defaulting to unkind motivations

misusing hidden motivations

Look for that post next Saturday!

Relatability is definitely more important than realism. Severance is unreal, but extremely relatable. Relatability is, unfortunately, something that's hard to teach, since it's a product of life experience and introspection. It's also one reason why some stories don't work across all cultures. There's a scene in Everything Everywhere All at Once where two rocks with googly eyes talk about trauma. Extremely unrealistic, extremely relatable.

It is really critical. Thank you for sharing