Not Every Character Needs A Wounded Past (Part 2)

2 more types of characters who don't need wounds

Not Every Character Needs A Wounded Past (Part 2)

In Part 1, we looked at two types of characters who don’t require a tragically wounded past (Naive, Static) and the two elements most needed to enhance those types of character (Mentor, Exaggerated Counterpart).

Today, we’ll look at two more character types (Archetypal, Flawed/Weak) and two elements the help enhance those types (Unreality, Humor).

In the (paywalled) Workshop section at the end of the post, we’ll also look at one character who embodies all four character types, and whose novel makes use of all four enhancing elements.

3. Archetypal Characters Need Unreality

Some characters aren’t meant to feel like real people but rather like archetypes. This is true of Sherlock Holmes and other detectives, and it might also be true about Frodo and other fantasy-novel characters. (I talked about both Holmes and Frodo in Part 1 of this topic.) Their stories aren’t meant to be wholly realistic. Instead, they have a mythic quality to them, signaled by a level of unreality somewhere in the text: Holmes’ ability to draw entire narratives from seemingly insignificant details, Frodo’s home in the paradisaical Shire and his escape from forces of pure evil. In such fables, characters aren’t required to be complex; they’re mythical figures, stand-ins for ideas like “cleverness” or “innocence.”

Even in contemporary fiction, in familiar settings, archetypal characters emerge. In Emma Cline’s The Guest, Alex spends each day searching for a place to stay for the night. She steals from strangers and lovers, ruins expensive artwork, violates people and norms. She claims “there wasn’t any reason” for her offensive behavior, “there had never been any terrible thing” in her past. How, then, did she come to be such a helpless, callous, selfish person? A wounded past would explain her actions and make her into a sympathetic character. In absence of a wound, Alex is a cipher.

But she’s also able to represent an idea—that of the eternal guest—so that readers can move their focus from exploring Alex to exploring what it means to be powerless and shiftless, invited and then unwanted. Readers can draw parallels to real people who have had to rely on their ability to please others, either through their own faults or because they’re trapped in systems of inequality. Or maybe readers simply use Alex’s story to reflect on the anxieties that come with being a house guest!

The reason Alex feels like an archetypal character instead of a flat, unfinished one is that there’s a touch of unreality to her story. The plot feels dreamlike: Alex spends her time floating in the ocean, and taking floaty painkillers, and drifting from house to house. She keeps seeing terrible omens: spots of blood, a terrible pink stye in her eye.

While the events of the story are realistic (her dishonesty draws suspicion, her actions come with consequences), there’s a satirical exaggeration to the dialog (“Our art needs more technology and our technology needs more art”), and a dreamlike quality to the tone (“How odd the ocean was at night—strangely placid, the waves unfurling in polite afterthoughts on the sand”) that signals this story is one long, unending bad dream. In fact, the story never comes to a resolution, much to the displeasure of many readers (though not this one).

Archetypal characters certainly can have wounds. (To me, Katniss Everdeen reads as a bit of an archetype, for example, and she is quite wounded by a childhood absent of parents and food.) But an archetypal character without a wound needs to exist in a story that’s somewhat unreal if we want to signal to readers that this character is meant to represent an idea and not an actual person.

4. Flawed/Weak Characters Need Humor

While flawed characters often have wounds, they don’t require wounds. They might have been shaped by a past tragedy, but that tragedy doesn’t have to have left them wounded.

Famously, the opening of Emma tells us that the titular character bears not a single wound: “Emma Woodhouse, handsome, clever and rich… had lived nearly twenty-one years in the world with very little to distress or vex her.” It’s true that Emma has grown up without a mother, but Emma’s governess has stepped in to fill that void, treating Emma with “affection” so that Emma has “no more than an indistinct remembrance” of her mother, a fact that is never reflected on with sadness.

Although her mother’s death hasn’t wounded Emma, it has led to Emma’s greatest flaw: she has “rather too much of her own way.” Emma will go on to meddle in everyone’s romantic affairs, to ridicule a poor neighbor, and to accidentally break the heart of the local vicar (until she’s finally schooled into greater maturity by her mentor and love interest, Mr. Knightly).

Emma’s flaws don’t point toward a sad past or a pained deficiency; instead, they’re generally funny and charming, as are her father’s flaws. Perhaps because of his wife’s premature death (this is suggested more by the miniseries than by the novel), Mr. Woodhouse is overly cautious about matters of health, to the point that when he attends the governess’ wedding, the cake becomes “a great distress to him” and he “earnestly tried to prevent anybody’s eating it.” Such a great bit of subtle humor!

When the worst event of a character’s past leads to more humor than pain, we can forgo thinking about wounds and instead focus on flaws. If we don’t see characters experiencing real pain as a result of a past wound, we’re able to laugh instead of cry, and this laughter is often a way of acknowledging not only the characters’ flaws but our own. (Aren’t we also a little vain and meddlesome, a little too phobic in matters of health?)

For some characters, this vague wound leads not to flaws but to weaknesses—vulnerabilities that they have no recourse against. More on this in the Workshop section below.

Either way, a terrible past event doesn’t always need to create a tragic character. Flawed (or weak) characters can be fascinating without any wounds. ●

Your Turn

If you’re looking to enhance a character who has no wounded past, ask yourself these questions:

What idea might my character represent, and how can the setting or plot reflect that?

How can I illustrate my character’s past misfortunes to comic effect?

A Deep Dive into the Character With No Wounded Past: Charlie and the Chocolate Factory

Let’s look at how the main character from an enduring children’s story manages to serve as an effective stand-in for the reader.

Charlie Bucket embodies all four character types (Naive, Static, Archetypal, Weak), and Charlie and The Chocolate Factory makes use of each of the four elements needed to enhance those types (Mentor, Exaggerated Counterpart, Unreality, Humor).

1. Naive

In the beginning of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, Charlie knows nothing about the factory and must be mentored by Grandpa Joe, who tells Charlie rumors he’s heard about how the place runs. This allows the reader to learn about the bizarre factory before Wonka enters the story and takes Charlie (and the reader) on a dizzying tour.

Once Wonka announces that he’s hidden five golden tickets inside random Wonka candy bars, Charlie and Grandpa Joe are eager to find a ticket, but they know their odds are slim, since they have so little money with which to buy candy bars. Grandpa Joe tries to help Charlie deal with the pressure of searching for a golden ticket: “Just forget about all those golden tickets and enjoy the candy.” Wise advice.

However, it’s really the other children in the story who provide the mentoring for the reader. Each of the children who wins a golden ticket and tours the factory, except Charlie, is terrible in a unique way. Greedy, spoiled, obsessed with gum, glued to television. (The four cardinal sins of childhood, apparently.) The reader, presumably also a child, is meant to learn to reject these qualities and be more like Charlie, who is grateful for every chocolate bar, who carefully observes Wonka’s rules, and who is generous enough to share his food with his family, even when he’s starving.

2. Static

Charlie doesn’t change or grow over the course of the story. From the time he enters the chocolate factory, almost all his dialog is some variation of “Look, Grandpa!”

By the end, his circumstances have changed drastically (he inherits Wonka’s factory), but his character is otherwise the same in every way. (The movie shows him breaking a rule in the factory by sneaking a fizzy lifting drink, but even then, Charlie proves his honesty by returning the everlasting gobstopper instead of stealing it for a bribe from Wonka’s competitor.)

Charlie instead provides a stand-in for the reader during the tour of the factory. The factory itself is outrageously weird, as is Wonka. Wonka is Charlie’s exaggerated counterpart, a maniacal character who looms much larger than our boy-hero, a man who lives among chocolate while Charlie himself has very little to eat.

Charlie has other exaggerated counterparts: the children who accompany him on the tour but who, unlike Charlie, break Wonka’s rules. These children have such exaggerated flaws that the reader is treated to a bizarre parade at the end of the novel, as the children leave the factory looking literally “thin as a straw” (greedy Augustus), “purple in the face” (gum-chewing Violet), “covered with garbage” (spoiled Veruca), and “ten feet tall” (television-obsessed Mike). The reader feels very virtuous in contrast, as virtuous as Charlie.

3. Archetypal

Charlie doesn’t seem like a realistic child. Even when he has very little to eat, he shares his bread with his mother. On his birthday, the only day of the year he gets a taste of the chocolate he perpetually hungers for, he tries to split the bar with his grandparents. Although he’s literally starving, he never steals food, and even in the chocolate factory, where he must still be starving, he never over-indulges like the other children. When he’s told he has won ownership of the factory at the end of his tour, he initially refuses the coveted prize because his bedridden grandparents wouldn’t be able to come with him.

The story, then, is a fairytale. Charlie is perfectly virtuous from start to finish, and his virtue is rewarded (with ownership of the factory at the end of the story). The other factory guests, caricatures of unvirtuous children, are thoroughly punished. These archetypal “good” and “bad” children are models for the child reader. When the oompa loompas who work in the factory appear every so often to impart a lesson in the form of an irreverent song, they seem to direct their mentoring not toward Charlie (who is already good) or even toward the other children (who seem unreceptive to scolding) but toward the young reader: “Dear friends, we surely all agree / There’s almost nothing worse to see / Than some repulsive little bum / Who’s always chewing chewing gum.”

The unreality of the story is apparent in the strangeness of Wonka and his factory. Wonka plays the role of a magical creature—an elf, a fairy godparent, a wizard—who removes Charlie from the real world and its brutalities and transports him into a magical world filled with the very thing he’s been craving, all for the purpose of proving that children should be good if they want to avoid punishment and earn rewards.

4. Weak

Charlie has no character flaws, but he does have a terrible weakness compared to other children: he’s very poor. His Grandpa George explains why this bars Charlie from any hope of winning a tour of the chocolate factory: “The kids who are going to find the Golden Tickets are the ones who can afford to buy candy bars every day. Our Charlie only gets one a year. There isn’t hope.” (Grandpa George is a more cynical mentor than Grandpa Joe.)

But Charlie’s situation isn’t shown as tragic. The revelation that Charlie “felt” his family’s poverty “worst of all” is immediately countered with the somewhat funny admission that “the one thing he longed for more than anything else was… CHOCOLATE.” The all-caps is the original formatting!

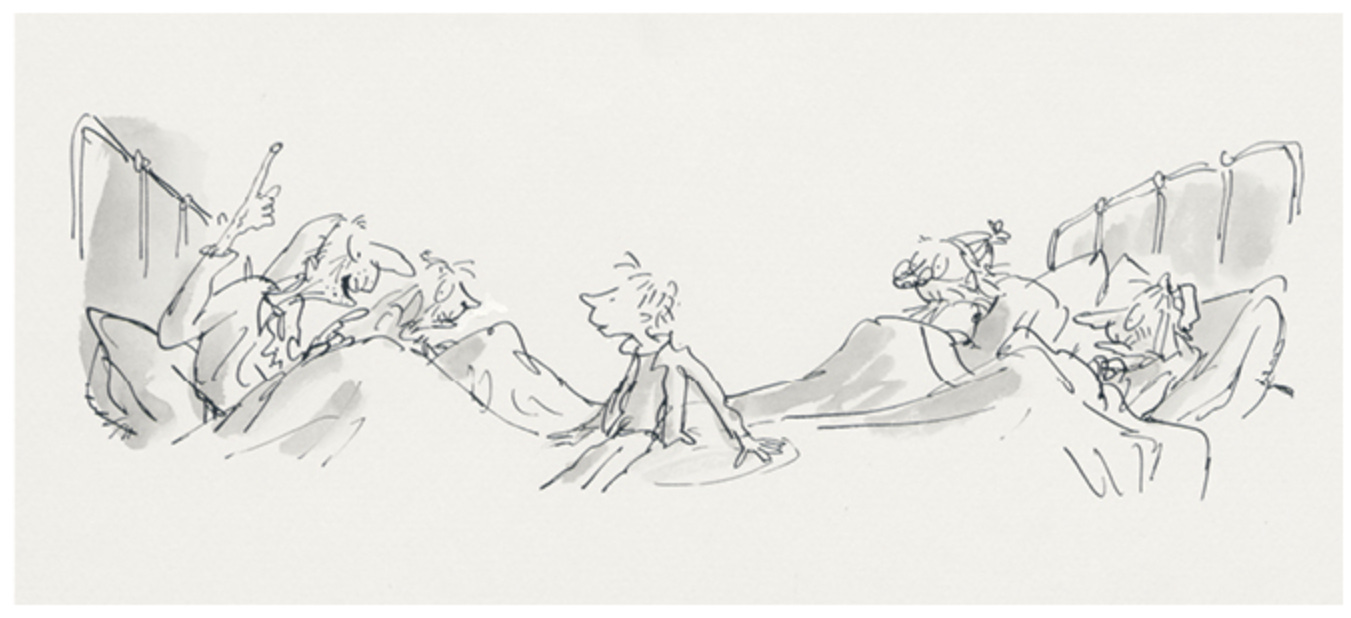

His family’s poverty is even presented as somewhat funny. His four grandparents all share one bed, an absurd situation made more absurd by Quentin Blake’s scribbled illustrations. Charlie’s father, the breadwinner, works in a factory where he screws caps onto toothpaste tubes! He must screw on the caps as fast as he can, but “however fast he screwed on the caps, [he] was never able to buy one-half of the things that so large a family needed.” The image here is comical, even while it makes Charlie and his family into very sympathetic characters.

Even when Grandpa Joe scrounges up enough savings to buy Charlie another chocolate bar, and they open the wrapper to find they have once again failed to win a Golden Ticket, there’s no tragedy. Instead, “they saw the funny side of the whole thing.”

The humor in the story is only critical when it comes at the expense of the “bad” children. Otherwise, it’s reassuring, providing child readers an escape from their own “weakness,” which is inherent in being young and powerless.

Charlie is a character without a wounded past (or in any case, his poverty is presented through a humorous lens). He’s naive to the ways of the world, untainted by the corruption the other children in the story suffer under. He’s static enough to provide a stand-in for the reader; he’s a vehicle for wish-fulfillment. As the archetypal “good child,” he affirms the idea that children should be humble and grateful and obedient. His situation is always fun and funny, so that child readers can feel assured that their own disadvantage as weak creatures is countered by the rewards their goodness will surely attract. ●